|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

THE DRAGON OF THE SUN: AN ORAL HISTORY

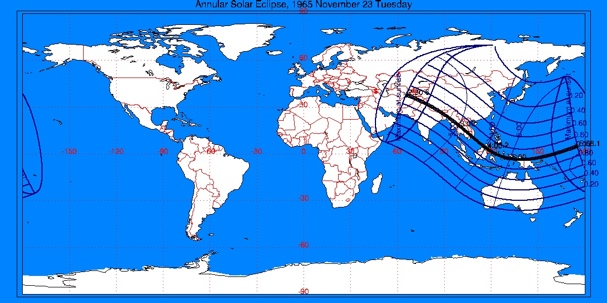

Here is an account of a solar eclipse, as seen by a band of nomadic Penan. The story itself is quite extraordinary; and the circumstances under which I collected it are sufficiently interesting to justify quoting the diary entry in which I describe them. I wrote this entry on December 6, 2009, the day after I got back to Miri, a major town in Sarawak, after a month in the company of Galang. Galang has been my friend and mentor for almost a decade. "Two of the most interesting "eureka moments" occurred today, in short order, thanks to the internet. Galang had told me a story from his childhood about a solar eclipse he had seen. Of course as soon as I got to town I Googled a website listing all eclipses in the 20th century, and the places where they were visible. According to Galang, this event must have happened in the 60's or 70's, so I scrolled through all those listed, and no mention was made of either Malaysia or Borneo. My heart sank. Could this have been a piece of fiction? I tell him many things about the world, including science; he is a very curious man, and among other matters I have explained eclipses. Furthermore, he has some schooling, and seemed acquainted with the Malay word for the phenomenon. Could he have simply constructed this story? And if he had, this would call into question not only his integrity, but in fact every single thing that he has ever told me. That would be serious! I have spent years of my life as his student. But the evidence here would be necessarily conclusive. Either this part of Borneo was in the path of an eclipse during the appropriate period, or Galang is an inventor of tall tails. There is no way to fudge a middle path here. "So I went to another website, this one that actually shows pictures of eclipse paths for every event in the 20th century. I scrolled down it, clicking on each date in turn, until I reached 23 November 1965. A chill travelled up and down my spine, and my eyes reddened. An annular eclipse, its narrow path crossing Penan territory at the very middle of its length -- around local mid-day. Close enough to the 10:30 or so he estimated (they had no watches then!) And close enough to his estimate of a 12-year old Galang (they had no calendars or birthdays either.) "Now here's the second "eureka moment". During the telling of the story, Galang reported that his father had seen circular or round ( beleleng ) images of the sun projected on the ground just before eclipse maximum. I had been sure that couldn't be right. I've witnessed four total eclipses myself, and understand optics and geometry. Just before totality, a small orifice -- pinhole, or tiny gap in the canopy -- would project the image of a crescent sun. It could not possibly be round. While he was dictating this detail, I was certain he had created some false memory. The scavenged zinc that roofs his shack is full of nail holes, and projects round images of the sun all the time. We have discussed these, and I have explained to him that these are actually images of the sun. "So after he had dictated this passage, I explained to him why this could not possibly be correct. In fact, I almost got short with him, so sure was I of my ground. But to his great credit, he stood his. He would not alter that detail of the narrative. He could have done so easily, just to please me. A lesser man would have. But not a man of his integrity. "Of course it turned out he was right. I had not been thinking in terms of an ANNULAR eclipse. An annular eclipse occurs when the moon is a bit too far away from the earth, and thus a bit too small, to cover the sun completely. Thus, it leaves a slender ring of bright sun around the silhouetted moon. A pinhole would cast an image of this in the shape of a ring -- which of course is round, circular. Another three or four shivers went up and down my spine. In every other detail as well, his story is an accurate description of an annular solar eclipse." WHEN THE DRAGON RENEWS THE FIRE IN THE SUN One day, long ago, when I was small, perhaps twelve years of age, some members of our band went out to cut heart of palm, others went hunting, and yet others went to fell sago palms, and cut their trunks into short lengths. Some people stayed in their houses. And some went to process sago into starch. Many of these people went to make sago at a river called Peresek. Another river they went to was called Pasui. Yet another was the Niting Stone River. It was to that river that my mother and father took me to process sago. So it was there that we set to work. This river was not far downhill; it was close enough that a person making a pheasant's call in one of the houses could be heard from where we were working. My siblings (all younger) remained in our house, because they were not strong enough to travel. They stayed there with our grandparents, who took care of them. Only my parents and I went out to make sago. My father set to work splitting the lengths of sago trunk in half. He split two lengths, and I started adzing one of the four halves. My father began adzing too, and once there was enough pith, my mother began to tread it, while my father sat near her, on the discarded sago bark (scooping up water and pouring it over the pith, to extract and dissolve the starch which then filtered through and collected in the lower of the two sago mats.) Then my father took his machete to sharpen the end of his sago adze. I was sitting on one of the discarded lengths of bark. Once my father had finished his sharpening, he, too, sat down, watching my mother tread, and examining the water with its dissolved starch as it dripped into the lower mat, to see if the sago was going to be good or not. In the old days we did not have watches. So we would have said that it was the time of day that the eagle whistles. Today, we would say something like 10:30. And then my father saw something on the leaves we had laid on the ground to collect the adzed pith, and also on the discarded lengths of bark. It was like the sunlight that comes through tiny holes in a roof. It was circular, on the ground, on the bark, on the leaves. And at the same time the sky was darkening, as if real night were falling. In the river ravine the ngit cicada sounded, and so did the kerui cicada; as they do at dusk. Then my father said, "What is happening to the day? I think perhaps this day is turning to night." That is what he said to his wife. When the sky turned dark, I was greatly afraid. I did not even glance at the sun, not even once; for my father, who had looked at it, had said, "The sun is dark. There is only a little brightness around its rim. Why don't you two look at it as well, lest you think that I'm lying about this?" That's what he said to my mother and me, but we were very afraid, and neither of us was brave enough to look at the sun. My father spoke again. "What I saw was a sun turned dark, with only a little bit of brightness around it. If we don't leave right now, if we lag behind looking at it, perhaps the dark part that I saw will spread, and cover the remaining bright part; then, I think, it really will be night. Let's hurry home right now, or we won't find your little brothers and sisters; I am afraid your mother and I will not find our little children." That's what my father said. That was why my father led us back without delay, for he feared that the darkness would spread and cover all the sun, and bring night. That was his thought; that is what he guessed would happen. By good fortune, it did not turn out that way. It did not become black like night. So my father made a pheasant's call to those upstream, and also to those downstream, to tell them that the day was turning to night. So my father took us home, and we left all the shredded pith behind. We left the processing platform behind, along with the pith lying in the upper mat. All the people went home. Those who were far away, like those who had gone hunting in a distant place, just stayed there. Those who were near the house, those who had gone to make sago or harvest heart of palm, immediately ran back to their houses. And there they all gathered, on the sitting deck built in the space between the houses. Some of the people did not move, frozen in fear. So they sat there, looking into the air, at the sky, at the sun; and in just another minute or two the light of early morning appeared, and the ngangit bird made its call, as it does every morning. And some of the people saw that the day was growing brighter once again. And they said, "It is good. The spirits will preserve us once again." So they were glad. And they stayed there until the sun had descended halfway. Nowadays, instead of saying "the sun has descended half way," we say "about two o'clock." Then they remembered all of the sago mats and shredded sago pith they had left behind in their flight. So they want back, and adzed the remaining trunks, and trod the remaining pith, and after they had finished they returned to their houses once more. And they stayed there, and evening came, and night fell. And they discussed the day that had turned dark, and they all decided it was evil, and a cause for fear. When the new day came, four from among them set forth to visit another band, to bring the news of the day that had turned to night. But the people they visited said it had been quite the same for them as well, and that they too had all been afraid. So they stayed overnight with that band, and on the following day, four members from there joined the original four, and the eight of them set forth to visit a third band. There lived a man who remembered the old stories; and he knew magic as well. And he also understood what had happened. In his youth his name was Beluluk; once he had a child, his name became Father of Surut. So the people who had decided that the day that turned to night was evil, and to be feared, talked to Beluluk, and this is what they said: "All of us took lumps of sweat bee wax, or lumps of damar resin, or lumps of sap, or rotten leaves, or the peeling bark of the belavan tree; and we said to ourselves, night is surely falling, and these things we will use by way of torches to light our way home. That is what we were thinking, as we were travelling in the forest when the day grew dark." That is what they said to Beluluk, because they were in great fear, worried that day would turn to night forever; and if day should turn to night forever, there would be no way to hunt game, or find other kinds of food. Because of that, they were very worried. "That is the opinion of all of us there," they said to Beluluk. Then Beluluk spoke. "There is something that a headman called Nyagung said in the old days. Nyagung knew magic. I, too, know magic," said Beluluk to the people who had said these things. "What they say, and what the spirits say, is that when the sun goes into shade, and it looks as if night is coming, this is the dragon spirit coiled around the sun that is renewing the old fire that is almost spent. This is the dragon spirit that is giving new fire to the sun. If the dragon spirit did not replace the sun's fire, and the sun were spent, things would be very bad indeed. There would be everlasting night." So spoke Beluluk. "When it grows dark like that, may neither child, nor woman, nor man, panic at the sight, or be afraid. We can continue to live, because the dragon spirit that guards the sun is renewing its fire. This happens at intervals, when enough time has passed. It is like when we people, down here on the earth, see a fire log burn to its end; what we do then is light another, so that it can burn in turn. After we have lit it, and it too has almost burned itself out, we light yet another one. In this way too the dragon that guards the sun gives new fire, and gives new heat." Thus spoke Beluluk. "Somewhere in the future, not soon, but after a very long time, the day will surely come under shade, as if real night is about to fall. But it will not be real night. What you have seen is evidence that I speak the truth. What you have seen is not the only time that darkness will come in this way. What we are discussing here will surely occur again." Thus spoke Beluluk to those who had come to express their fear and agitation. To those who had been worried and afraid, it was like hearing the song of a bird, or taking a deep and relaxed breath. And each in turn grasped the hand of Beluluk, the man who had told them the reason why the day had darkened to the verge of night. From that day until this they have lived without worry and fear. Before they understood, they had thought that they were going to die, when, in mid-day, darkness had suddenly descended; they had thought the sun would be extinguished forever. "All of us people on the earth, all who live under the sky, will perish with no exception." That had been the thought in their minds. For the day had abruptly turned to night, and this had caused them great fear. Once they heard the words of Beluluk, they were relieved, and their hearts remain glad unto this day. This is one of many episodes of Galang's life that he himself has dictated. In the fullness of time it will be a chapter in his autobiography. Below is the story in the original Penan. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

BERUNGAN NGELIWAH LUTEN TONG MATEN DAU

Sahau hun ké' si'ik ngio ngio 12 ta'un umun ké', boh irah tamen tinen ké' ngan irah lem jepen ké' jelua' mé' moko tong lamin jelua' réh tai ala sin savit jelua' réh tai beté jelua' réh tai tebeng ngelo'ong uvut. Jelua' réh tai paleu. Pina réh tai paleu tong jah ba ngaran ba inah ba Peresek. Ngaran jah ba kepéh Ba Pasui. Ngaran jah ba kepéh Ba bateu Niting. Inah ba éh jalan réh tai paleu. Tamen ké' mihin amé tai paleu tong ba bateu Niting. Sinah mé' paleu. Bé' ju sa la'ut lamin. Poléng ha' kueu jin lamin. Padé ké' bé bé moko tong lamin uban irah bé' jak gahang lakau. Moko ngan po mé', po mé' nganan padé ké'. Amé teleu tinen tamen ké' awah tai paleu. Hun mé' avé sitai boh tamen ké' memila' lo'ong avé pat lo'ong akeu péh paleu jah bila' awah. Lepah inah tamen ké' paleu ja lo'ong jah bila' bé. Tinen ké' meték jah papah boh éh ala keruah papah boh tamen ké' menyun tong bangah teka'up néh déhé peluan. Boh tamen ké' ala po'é kenéh ngejipen paleu néh. Lepah éh ma'o ngejipen paleu néh nah akeu péh menyun tong jah bangah. Tamen ké' menyun posot tong jah bangah na'at tinen ké' nah meték tovo néh na'at litut uvut (=ba éh meto jin ja'an) jian atau bé' uvut nah jian. Uban sahau bé' pu'un jam, pajau dau para' pelakei hun inah. Hun ha' hun iteu, pukun jah polo vevilang. Boh tamen ké' na'at tong peluan avé tong bangah pu'un barei ada maten dau éh kivu upong sapau éh beleleng beleleng tong peluan tong tana' tong bangah tong ujung kayeu tovo inah langit semilep barei dau juk tahup mu'un tovo inah lem ba tong alo pu'un ha' ngit pu'un ha' kerui barei dau tahup poho. Lepah inah tamen ké' bara', "Ineu maneu dau ka'? Barang dau teu lah juk merem kio," ha' néh ngan redo néh. Hun néh semilep merem langit nah, akeu medai mu'un. Akeu bé' sapét ngelerit na'at maten dau uban ké' medai uban tamen ké' éh lepah na'at éh, iah bara', "Maten dau nah padeng rep rep. Si'ik mebéng pipa dirin néh," ha' tamen ké' bara' éh. "Tupat keteleu na'at éh hun iteu," ha' néh, "Dai néh ha' ké' pané awah, dai néh ha' ké' kenyo," ha' tamen ké' ngan amo tinen ké'. Amo medai mu'un lah. Amo tinen ké' bé' jeleng na'at maten dau. Boh tamen ké', ha' néh kepéh, "Uban néh ta'an ké' maten dau nah hun iteu padeng rep rep si'ik mebéng pipa néh. Hun tam bé' kelap laho, hun tam mobo da' na'at éh barang péh éh padeng ta'an ké' lem nah selep padeng telo'ong adang néh tio merem mu'un kio," ha' tamen ké', "Uban néh kenat hun iteu jak padeng rep rep. Pipa maten dau nah mebéng si'ik ke'. Hun néh selep padeng da', adang néh merem mu'un kio. Jian tam tio kelap molé dai tam bé' temeu ngan padé ko' éh si'ik dai amo tinen ko' bé' temeu ngan padé ko' éh si'ik anak mo éh si'ik," ha' tamen ké'.

Inah maneu tamen ké' tio mihin mételeu tio lakeu uban néh medai maten dau nah tio selep merem. Kenat éh seneruh néh. Kenat éh kenio néh. Okon jian bé' éh makat kenat. Bé' éh makat tio merem mu'un.

Boh tamen ké' ngueu ngan irah éh pina sa dayah avé sa ba'éng bara' dau nah juk merem. Boh tamen ké' mihin mé' molé kekat papah nepei sinah. Kekat tikan papah lem ja'an nepei sinah. Boh tamen ké' mihin jah itu nyateng pelayo lem gaweng néh nala jin lamin jalan néh juk kahang luten tong tikan boh mé' nihin néh molé kivu mé' lakau nah. Iah ngeradau bara', "Molé, tai lamin." Kekat réh éh molé. Irah éh lakau ju barei tai beté barei tai tana' ju irah tio moko sitai jak. Irah dani dani lamin irah tai paleu irah tai ala sin uvut irah tio nekedeu molé avé tong lamin. Boh kekat réh petipun tong patah tong belasek. Boh jelua' kelunan moko kejijen awah uban néh pua uban néh besau. Boh réh menyun sinah na'at tai sawang na'at tai langit na'at maten dau ngio ngio jah duah litep kenat boh pu'un peka nawa tovo inah péh boh ha' juhit ha' juhit ngangit miha' barei dau ngivun poho. Boh jelua' lah na'at kepéh lebé lebé dau nah tai nawa tai jian kepéh. Boh réh bara', "Jian lah. Balei juk purip uleu keto," ha' réh. Boh réh bahu boh réh moko ngio ngio tai dau kuba' vevilang uba' boh réh tai hun dau vevilang uba' ha' réh nah hun iteu ngio dau pukun duah. Boh réh pekenei kenin réh atau petesen atau nesen kekat tabau kekat papah nebet réh kelap ni'ei rai. Boh réh tai kepéh paleu bila' éh lepah ri' ngan meték papah éh lepah ri' boh réh ma'o lah boh réh molé tai lamin. Boh réh moko boh dau tahup boh dau merem irah mingang tosok dau nah merem ri'. Kekat réh kua' mingang éh sa'at, kedai réh. Hun dau rema irah jelua' ngio pat usah tai nepah tong jah jepen kepéh bika' atau perengah dau nah merem ri' ngan irah tong jah jepen kepéh. Irah péh kua' bara' éh kenat pata medai bé bé. Dau inah irah mepai tong jepen inah. Pat usah kepéh jin jepen inah peseliko ngan pat usah ngan jepen éh lepah ri' tai tong jah keteleu betah jepen kepéh. Sitai pu'un jah usah irah éh nesen ha' tukit ngan ha' tosok ngan inah péh lakei inah renget. Iah péh jam ayo néh. Ngaran néh Beluluk hun néh lemanai, hun néh pu'un anak ngaran néh Tamen Surut. Boh irah éh mingang ngan medai dau nah sa'at layan juk merem mu'un ha' réh tosok ngan lakei ja'au Beluluk nah, ka' ha' réh: "Kekat amé rai pu'un amé ala bukuh nyateng lengurep. Pu'un mé' ala bukuh nyateng pelayo. Pu'un mé' ala bukuh nyateng pelep. Pu'un mé' ala borok ujung da'un. Pu'un mé' ala ipa belavan, ha' lem kenin mé' hun dau merem da' inah éh seleket mé' inah éh titui mé' molé tai lamin, kenat ha' lem kenin mé' hun mé' lakau tong tana' sio dau merem iteu rai kei," ha' réh tosok ngan lakei ja'au Beluluk nah, uban réh besau uban réh pua medai dau nah merem pelinguh irah seruh éh hun néh merem pelinguh bé' lah pu'un jalan pitah ka'an atau paleu pitah belunan. Uban néh kenat irah besau mu'un lah. "Kenat ha' kekat amé éh sitai kei," ha' réh tosok ngan lakei ja'au Beluluk nah. Boh Beluluk nah tosok. "Pu'un jah ha' pengeja'au lu' sahau ngaran néh Nyagung. Nyagung nah péh renget sahau. Akeu péh to renget," ha' Beluluk nah ngan réh uban réh tosok kenat. Boh Beluluk nah bara', "Ha' réh ngan balei bara' éh, hun maten dau nah semilep lihep ngan barei juk merem kenat inah balei berungan éh keléléng pipa maten dau nah ngeliwah luten néh éh lepah nah juk bé. Inah balei berungan nah mena' jah luten maten dau nah maréng kepéh. Hun balei berungan nah bé' ngeliwah luten maten dau nah hun néh tio bé inah boh éh sa'at mu'un. Inah boh éh omok merem pelinguh," ha' lakei ja'au Beluluk nah. "Hun néh merem kenat awah jak mai anak mai redo mai usah tam lakei pua atau besau na'at éh. To ke' tam omok murip uban balei berungan éh mava maten dau nah éh juk ngeliwah luten néh maréng kepéh. Siget siget kelebé hun néh sukup kelebé barei uleu kelunan éh tong tana' teu hun lu' suai jah satek bupen kayeu meden adang hun lu' na'at éh juk popot bé adang lu' seket jah satek kepéh doko néh mahang ngan meden kepéh. Hun lu' seket éh kenat hun néh juk bé kepéh uleu seket jah kepéh. Barei inah ayo berungan éh mava maten dau nah mena' luten néh maréng mena' ada kepana néh maréng." Kenat ha' lakei ja'au Beluluk nah tosok. "Hun mah mah péh vam bé' éh laho sukup kelebé adang pu'un dau nah kepéh semilep lihep barei juk merem. Tapi' bé' éh merem mu'un kepéh. Inah telana' néh ha' ké' mu'un. Bé' éh jah kolé iteu awah, éh merem kenat. Adang néh pu'un kepéh jin ka'o tam pepané tam petosok iteu vam," ha' lakei ja'au Beluluk nah pané ngan irah éh tai bara' kepua bara' kebesau réh ri'. Boh irah éh medai éh pua éh besau nah barei pu'un ha' juhit nenéng barei pu'un ibot éh jian kepéh. Boh réh tabi' ngan lakei ja'au Beluluk éh tosok éh bara' gaya' dau nah éh juk merem nah. Boh réh lah moko lepah réh menéng ha' kenat boh lah réh molé boh lah réh tosok éh ngan kekat lua' réh tong jepen réh. Boh kekat irah lua' réh tong jepen bara', "Hun kenat uleu omok murip jian. Uleu omok pu'un penesen. Uleu omok pu'un ida. Pu'un ava' kepéh belah kekat jepen lu'," ha' réh. Boh lah réh jian kenin. Kekat irah Penan lah mihau ha' inah ngan nesen ha' réh tosok inah. Jin sahau avé hun iteu inah maneu réh bé' pua atau bé' besau. Bu'un bu'un sahau hun réh bé' jam éh irah seruh éh matai awah uban dau nah merem ulak dau ja'au irah seruh éh pemata' maten dau nah pelinguh. "Kekat lu' kelunan pah tipo tana' ra' langit matai bé," ha' kenin réh. Uban dau nah beka' tio merem awah. Inah maneu réh medai mu'un. Hun réh lepah menéng ha' lakei ja'au Beluluk nah tosok kenat, boh réh bahu ngan jian kenin lah avé dau iteu. |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

return to

Myths and Legends

|

|||||||